Mighty Words

Hungary's Great Anti-Migrant Campaign

Illustration by Joy Lau

Throughout 2015 and 2016, residents of Hungary — a European Union member state in Eastern Europe — could feel that they have been involuntary participants in a gigantic social psychology experiment about the power of propaganda. In response to the implications of the global migration crisis for Europe and the European Union’s plan to resettle refugees among its member states, Hungary’s current government launched a full-scale propaganda campaign to set the country’s residents against the refugees and the EU. The messages included: “Did you know that Brussels wants to settle a city’s worth of illegal immigrants in Hungary?”

The campaign went full blast in July 2016, as an unnecessary referendum was announced by the Prime Minister for early October to boost the domestic political support of the ruling party and it’s anti-migrant policy. In this period, Hungarian residents were continuously bombarded with harsh propaganda. The messages of the government were delivered through various instruments, including billboards, TV ads, pamphlets, and the heavily biased coverage of the pro-government partisan media. The government campaign — which, experts estimate, alone was costlier for Hungary with a population of 10 million than the whole ‘Brexit’ campaign was for the UK with a population of 64 million — generated fear and hate.

The propaganda made the Hungarian society vulnerable to false claims about Western Europe’s no-go zones, rape incidents, and terrorism. Meanwhile, the more sophisticated techniques of manipulation could go almost completely unnoticed. How could the language of the Hungarian propaganda covertly influence the society’s thinking? This blog entry introduces briefly the most crucial rhetorical devices that were employed in the recent Hungarian propaganda campaign. The analysis of the Hungarian case may highlight some general linguistic mechanisms and patterns concerning anti-migration discourses in general and anti-EU discourses within the European Union in particular.

1. “The Brussels Metonomy”

In the campaign, instead of the European Union, the Hungarian propaganda consistently referred to “Brussels”. Normally, this would not be surprising. We often refer to foreign powers by capital cities. This widespread technique is called metonymy. One can refer to “Beijing” instead of the Chinese Communist Party or use “Washington” for the American government. However, in the Hungarian case, the reference to “Brussels” is not neutral. Hungary is part of the EU. In this regard, the country itself represents “Brussels”. Yet, the “Brussels metonymy” creates the false impression that the EU is a foreign power for Hungary. The reference to “Brussels” also evokes historical memories of the periods when Hungary was ruled by the Habsburg-dynasty (“Vienna”) or controlled by the communist Soviet Union (“Moscow”). Playing on the old labels, the “Brussels-metonymy” manipulates the Hungarian society into thinking of the EU as the new “Vienna” or “Moscow”.

2. Framing: the “Brussels Elite” and the “Brussels Bureaucrats”

The Hungarian propaganda also often referred to the “Brussels elite” and the “Brussels bureaucrats” in the campaign. As the American linguist George Lakoff highlighted, when we hear or read a word, it evokes conceptual frames in our mind. Words influence our thinking through such frames. The previous labels, for example, encourage the Hungarian population to think of the EU as an obnoxious, narrow-minded, foreign power. The reference to the “Brussels elite” indicates that the Hungarians are ruled by a small group of rich and privileged foreigners. Meanwhile, the label “Brussels bureaucrats” implies that Hungary’s faith is in the hands of some rigid, heartless foreign officials who are detached from the reality. These references completely distort and portray in a very negative light the transparent democratic procedures of the EU in which the equal member states — including Hungary — participate.

3. The Migrant Stigma

Besides “Brussels”, the propaganda in Hungary targeted the people who flee their countries. Oftentimes, they have been identified as “migrants” (“migráns”) by the government and its media. This technical term may sound unfriendly to the ears of many Hungarians. Also, “migrant” is a foreign word in Hungarian and hence can underline that the migrants “differ” from the locals (“even their name is strange”). Accordingly, in the vocabulary of the Hungarian government and its media, since 2015, the word “migrant” is not a neutral term but a stigma. It reduces the refugee women, men, and children to one single, impersonal, and repulsively represented status. It is no surprise that the word follows the typical career path of derogatory labels, being widely pronounced today in Hungary in a slightly distorted form (instead of “migráns” as “migráncs”). The distorted version of the term “migrant” is an open verbal abuse against the refugees which can be associated with offensive and insulting labels such as “nigger” or “chink”.

4. The Illegal Immigrant Stigma

The Hungarian propaganda also frequently identified the refugees as “illegal immigrants”. This label was not used as a technical term either. The word “illegal” evokes the frame of “unlawfulness” in the mind, representing the masses of innocent people who are running for their life as dangerous and fearsome criminals.

5. Nominalization

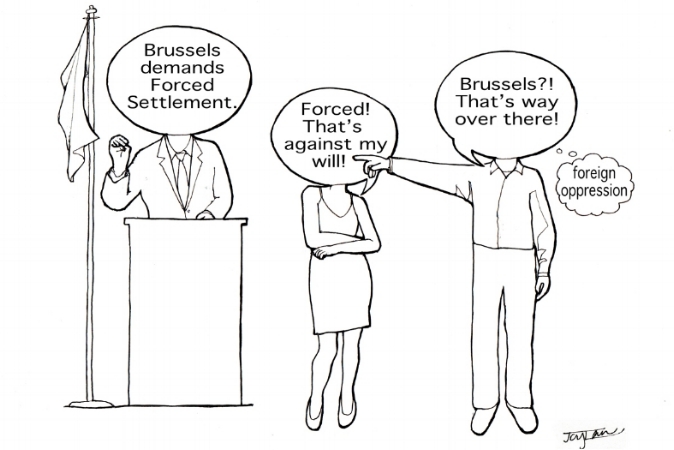

The propaganda in Hungary campaigned against the “forced settlement” (“kényszerbetelepítés”) of migrants by the EU. However, “forced settlement” has never been on the EU’s agenda. Still, in Hungary many believe that the “forced settlement” is an existing, actual danger. This is partly due to a common manipulative technique called “nominalization”. The word “forced settlement” is a noun. Usually, we use nouns when we talk about existing entities. Therefore, if a word takes the form of a noun, the listeners will take it for granted that it refers to something real. The word “forced settlement” was used arbitrarily by the Hungarian propaganda. Yet, being a noun, the concept could easily be perceived by the society as reality.

Illustration by Joy Lau

6. The “Forced Settlement” Frame

The word “forced settlement” is a compound word and both of its parts evoke negative feelings (“settlement” in Hungarian has traumatic historical connotations). Additionally, the expression “forced settlement” activates the frames of additional Hungarian compound words that partner with “forced”. The relevant expressions concern such brutally coercive measures against individuals as “forced eviction” (“kényszerkilakoltatás”), “forced labour” (“kényszermunka”), or “forced drugging” (“kényszergyógykezelés”). Through these associations, the word “forced settlement” evokes the frame of “involuntariness” in the mind, generating an instinctive, bodily rejection in the listener. In this regard it is not irrelevant that in the Hungarian referendum citizens were asked if they “want” the mandatory settlement of migrants. Who would “want” coercion?

7. Metaphors: “Blackmail”, “Push”, “Pressure”

Throughout the campaign, the Hungarian propaganda portrayed the EU as an oppressive power via metaphors as well. Metaphors present one thing in terms of another, shaping people’s ideas. In the context of the migrant crisis, the Hungarian government, for instance, presented to the local population the EU’s transparent, proper, and democratic procedures — in which Hungary participates as well — as blackmail”, “push” and “pressure”. These metaphors strengthen the impression that the EU is an aggressive power and covertly encourage local people to reject its migrant policy.

8. Attacker-Attacked Reversal

When the Hungarian government represented the EU as an oppressive power, it employed a popular rhetorical device called “reversal”. It allows speakers to assign the role of the attacker to those whom they themselves actually attack. The Hungarian government arranged the anti-migrant referendum to put pressure on the European Union. Accordingly, in the referendum campaign the government introduced a slogan that openly threatened the EU: “Let's send a message to Brussels so that they understand.” Fist shaking could be accompanied by such words. Yet, the Hungarian government reversed the actual set-up and created the impression that the real aggressor is the EU: “We reject Brussels pressure!” The attacker-attacked reversal supports positive self representation. It is tempting to identify with the likable role of the victim instead of appearing to be the aggressor in a conflict.

9. The “Stupid EU” Implication

The Hungarian propaganda constructed the EU not only as an oppressive power but also as a naive, stupid and dumb power. The slogan “Let's send a message to Brussels so that they understand” implies for example that the EU is inferior to Hungary in intellectual terms. Similar to the victim-role, this implication offers Hungarians a very flattering self-image.

10. The State of Emergency Rhetoric

Hungary’s government used exclusively a “state of emergency rhetoric” to frame the European consequences of the migrant crisis. Words that could activate the frame of humanitarianism (“shelter”, “food”, “protection”, “family reunion”, “children”) were completely absent from the campaign for instance. The vocabulary of the Hungarian propaganda (“danger”, “danger of terrorism”, “no-go zones”, “rapes”, “epidemics”) merged facts which were taken out of context with lies, as well as blurred the difference between “migrants” and "terrorists”. These words evoked the frame of a “state of emergency” in people’s mind, creating the false impression that in Western Europe the migrant crisis brought complete lack of order, chaos, and even lawlessness. On these grounds, the propaganda tried to present the referendum to the population as the last and only solution to avoid the collapse of the Hungarian state. As it was put in a slogan: “Brussels must be stopped!” This dramatic exclamation indicated that the referendum was a narrow escape.

Illustration by Joy Lau

Hungary’s referendum was eventually invalidated as fewer than half of the voters cast a ballot. Of these, 98 percent supported the government’s position. Meanwhile, a significant number of people cast invalid ballots or consciously stayed away from the polling stations. This background did not prevent Hungary’s government from celebrating the invalid referendum as a “huge success” and to amend the country’s constitution.